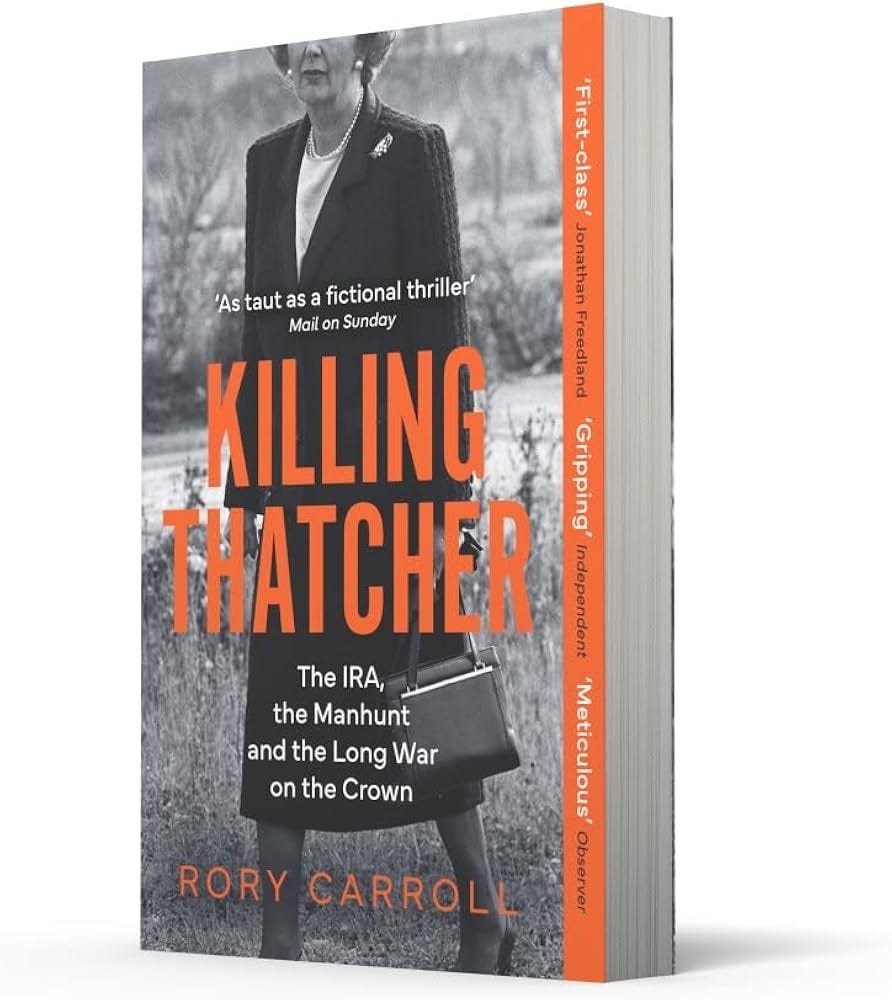

Killing Thatcher

On focalisation vs point of view and how 'narrative' narrative non-fiction actually needs to be.

I’ve just started reading Rory Carroll’s brilliant work of narrative non-fiction, Killing Thatcher and it’s incredibly compelling, dramatic, atmospheric, sympathetic as well as being well-researched, informative and authoritative. In short, it’s the kind of writing I love.

Something friends and students have difficulty with is distinguishing narrative/creative non-fiction from non-fiction. I don’t blame them – these days the boundaries are becoming increasingly blurred – it’s not like the old days (see Theodore Roosevelt’s auto-biography) where non-fiction was told from the safe distance of hindsight and relayed in a big infodump.

Most memoirs and biographies these days have at least a more narrative feeling sense of structure and often employ the cinematic and literary techniques we’d more traditionally associate with dramatic narrative; things like use of symbolism, foreshadowing, dialogue, pacing, tension, actions and perhaps most importantly, scenes.

Something I’ve been struggling with – or probably more accurately, trying to calibrate – given that the agon is an inevitable part of what kind of story our research allows us to tell – is this question of narrative distance that I touched on in a previous post, Other People.

In writing a narrative account of the Shannon Matthew’s kidnap, When lights Are Bright – a story in which a working-class mother abducted her own daughter and opened up a glimpse into the complex inner working of class, identity and morality in modern Britain. In an ideal world, I would have personal relationships with the key players – especially Shannon’s mother, Karen – and write the story in their own voices, something like Norman Mailer’s Executioner’s Song (1979).

Instead, the distance has to be more removed and liberties can’t be taken with what characters are thinking or feeling… unless that’s been documented or relayed to me in the course of my research. It means unlike many novels, interiority is out of the window and the narrator has to do more of the legwork. It also means in terms of storytelling technique, a key change in perspective.

Point of View vs Focalisation

Because perspective/point of view can mean many things, the French theorist Gérard Genette coined the term ‘focalisation’ to replace it. His rationale was to avoid confusion around who sees? and who speaks?

For Genette, zero focalisation is where the narrator knows more than the characters, even sometimes including their thoughts and actions. It’s very similar to an omniscient narrator and the point of view isn’t focalised (limited) to any particular character because the narrator knows everything. This tends to be the case with traditional histories, for example.

Then you have variations of internal focalisation: this can be fixed or limited to one particular character’s perspective, it can be variable and shift between several characters or multiple focalisation – which would the the same event or events told multiple times through different character’s perspectives.

If internal focalisation is about telling a story from within a character’s perspective without much (or any) meditation of a narrator, external focalisation is where a narrator is used and they don’t necessarily have access to the character’s inner thoughts or feelings:

Homodiegetic, a character in the story.

Heterodiegetic, not a character, but knows a lot about the story.

Autodiegetic, homodiegetic narrator who is also the protagonist

Coming at narrative non-fiction from the background of a fiction writer, it’s very tempting for me to focus on internal focalisation and I have a desire for what’s revealed to emerge from character-bound perspectives but this is something that doesn’t always happen in narrative non-fiction where much of the narration has to come externally.

So, Killing Thatcher (renamed ‘There Will Be Fire’ for the US market), begins not like a history/biography with the assertion of a thesis or facts, but with a scene that feels like it could be from the pages of a thriller:

A light breeze salted the Brighton seafront when the taxi carrying Patrick Magee pulled up outside the Grand Hotel.

The driver opened the trunk and gave a cheerful warning to the porter, who reached for the case. “You’d better hold on to your nuts for this one, you’ll need ’em.”

It was just after noon on September 15, 1984, and it felt like the last day of summer. Sunshine burned through a residue of clouds, warming the pebbles on the beach. The English Channel glistened, serene. The Grand soared over King’s Road like an overstuffed wedding cake, eight stories of eaves, cornices, and Victorian elaboration coated cream and white. A Union Jack fluttered from the roof. Built for aristocrats, it had hosted kings and presidents and film stars. Soon it would host Margaret Thatcher—and Magee had come to kill her.

Carroll, Rory (2023). Killing Thatcher. HarperCollins Publishers. Kindle Edition.

We are focalised (at least temporarily) within the perspective of Patrick Magee but it’s still external to him and would count as homodiegetic. But, unlike many novels, Carroll doesn’t hang with him there throughout the book or even the same chapter. Within a few paragraphs, we launch into a longer stretch of heterodiegetic narrative:

FOR FIFTEEN YEARS, the IRA had been waging an insurgency to end British rule in Northern Ireland and to unite the region with the Republic of Ireland. It was the latest iteration of a centuries-old conflict between Irish rebels and their dominant neighbor.

In 1921, an earlier version of the IRA had expelled the British from twenty-six of Ireland’s thirty-two counties, paving the way for a republic ruled from Dublin. For Irish nationalists, it was as if a malignant cancer—an invasive force that had colonized Ireland’s land and people, ravaged its language and culture, poisoned the very idea of Irishness, all in the name of making Ireland British—had finally been excised. But, crucially, it was not gone altogether. The Union Jack still flew over those six northern counties. These were home to 800,000 Protestants—descendants of British settlers who had no desire to join a new independent state dominated by Catholics. So the British government carved out a statelet, Northern Ireland, that became a self-governing region within the United Kingdom.

The problem was that 450,000 Catholics in Northern Ireland felt stuck on the wrong side of the new border. Northern Ireland was run by Protestants for Protestants. The Catholic minority got the worst jobs and housing, and the government in London shrugged. When Catholics marched for civil rights in the late 1960s, police beat them. Riots escalated into an insurgency led by a revived IRA.

The IRA considered its campaign of bombings and shootings a war of liberation to end British imperialism and to unite Ireland. The British and Irish governments called it terrorism by republican ideologues who ignored the wish of most people in Northern Ireland to remain in the UK. By 1984, the conflict had claimed more than 2,500 lives and gained a euphemism: the Troubles.

Carroll, Rory (2023). Killing Thatcher: HarperCollins Publishers. Kindle Edition.

And so on for a thousand words or so.

In fact, much of the story is actually conveyed this way, between these methods of focalisation and using non-fiction to bolster the importance of the scenes and scenes to enliven the non-fiction.

Putting it all Together

When I sent out early drafts of When Lights Are Bright to write-friends, the feedback came in two varieties: the fiction writers wanted me to jettison the heterodiegetic passages that ‘read like Wikipedia entries’ and focus more on scenes and forward propulsion; while the non-fiction writers wanted me to focus more on asserting an argument and focussing too much on narrative propulsion meant sacrificing a more considered sense of character development and setting.

The work is a work of narrative non-fiction, and while some will always want more pace and action, the reality is the material and access might not be there. Being a work of non-fiction, for me at least, means your perfectly entitled to dish up some conventionally non-fictive writing, but so much depends on how well you create a sense of narrative tension using scenes as well as how well those scenes are supported, given context and gravity by the non-fiction. This understanding of focalisation has also liberated me from the shackles of internal point of view and let me trust in the narrator as a valid way to tell the story, and, as Killing Thatcher proves, it means you can tell a gripping story without the need to access the interiority of other people.