Other People

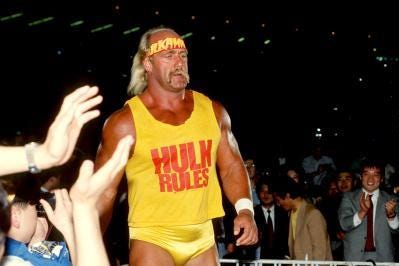

Some thoughts on the thorny issue of writing other people featuring Hulk Hogan and Marilyn Monroe.

Now it is autumn again; the students are all coming back. And as the dark evening cosmos and yellow fog rubs against the muzzle of the window-panes of the townhouse windows of Virginia Woolf’s former abode in 43 Gordon Square, I’m back teaching Creative Non-Fiction. In addition to some of the more theoretical blogs I’ve been posting about auto fiction and creative/narrative non-fiction, I’m going to be using this Substack to think about more practical questions of craft and reflect on some of the questions that arise during my seminars.

A couple of questions that came up this week is do I have to put myself in the text and the thorny issue of writing other people. The answer to the first is no: at least, not directly, you’re always in the text one way or another. As Will Self (I think) said, every novel is a memoir of the subconscious.

Still, even if you place yourself in the text, you don’t have to be spilling your guts, you don’t have to be the protagonist and you can maintain a level of narrative distance. The same goes for writing other people.

The novelist Emma Darwin is a brilliant writer but also a prolific and brilliant blogger on the craft of writing. She describes the levels of narrative (sometimes called psychic) distance here.

Essentially, it goes something like this:

On Sunday March 3rd, 1987, a large man stepped out of a Chevrolet Corvette in the carpark of the Pontiac Silverdome in Pontiac, Michigan into the Spring air.

Hulk Hogan could no doubt feel the buzz in the air as he stepped out of his car that night.

Hulk Hogan was buzzed about the show tonight.

Brother, thought Hulk Hogan, as he slammed the door on his ride. The Hulkamaniacs will be going wild tonight.

Brother, the hairs on his body stood on end. He slams the door shut and got out of the Corvette into the sting of heat and Wrestlemania buzz. Yards of concrete. The Silverdome ahead. Hard underfoot. Adrenaline pumps from your heart to the tips of your toes. 93,000 Hulkamaniacs are waiting for you.

It’s not the easiest trick to pull off but I think I’ve just about got it right.

Level 1 is much more factual and objective. There’s no interiority. These details can be fact-checked and we’re not entering anybody’s state of mind. The pros of this level of distance are the more documentary feel and it’s use for writing characters who you just don’t know there much about.

Level 2 introduces a degree of interiority (attributing a feeling, ‘buzz’) but it’s still mediated by the voice of a narrator (could no doubt feel), so we know there’s some kind of inference going on based on logical supposition. Sometimes, these kinds of attributions can be based on interviews/testimony/details from witnesses at the time.

Level 3 dispenses with the mediation and be have a strongish declaration of feeling (‘buzzed’).

Level 4 gets even closer, he have an attributed thought and then free-indirect-style, ie. the kind of language or phrases that the character would think and not the narrator (‘The Hulkamaniacs will be going wild tonight’).

Level 5 is more or less stream-of-consciousness. I’ve switched the tense to present to create even more immediacy. We’re in Hulk Hogan’s brain rather than watching from afar.

Now, these levels don’t necessarily have to be fixed and there can be a sliding scale but it needs to be carefully done and you can’t just slide in and out randomly. Some of this will be dictated by stylistic concerns but also what information you actually have, has the subject in question told you what they were feeling? Have you gleaned it from an interview?

In his true crime book, We Own This City about police corruption in Baltimore, James Fenton takes a fairly conservative, even tentative approach and sticks to Level 1, sometimes veering into 2 and 3 if and only if he has their thoughts/feelings on record. (Quotations are liberally littered throughout the text to the point of bringing you out of the moment at times). He’s still narrativising and writing in scenes but there’s distance:

Knockers

The letter arrived in the chambers of a federal judge in Baltimore in the summer of 2017. It had been sent from the McDowell Federal Correctional Institution, which was nestled in the middle of nowhere, West Virginia, more than six hours from Baltimore. On the front of the envelope, the inmate had written: “Special mail.”Umar Burley had written his letter on lined notebook paper, in neat, bouncy print, using tildes to top his T’s. Burley, inmate number 43787-037, was reaching out to the judge for a second time, begging for a court-appointed lawyer. His attorney had retired, and attempts to reach another had gone unanswered.

“Could you imagine how hard it is to be here for a crime I didn’t commit and struggling to find clarity and justice on my own?” Burley wrote.Months earlier, Burley had been in the recreation hall of a federal prison in Oklahoma, awaiting transportation to McDowell, when someone called to him: “Little Baltimore! Little Baltimore! Did you see that?” News from home flashed across the television screen: A group of eight Baltimore police officers had been charged with stealing from citizens and lying about their cases. The officers had carried out their alleged crimes undeterred by the fact that the police department was at the time under a broad civil rights investigation following the death of a young Black man from injuries sustained while in police custody. The revelations were breathtaking, though not entirely unbelievable: For years, accusations of misconduct—from illegal strip searches to broken bones—had been leveled against city police. But many claims lacked hard proof and came from people with long rap sheets and every incentive to level a false accusation. Such toss-ups tended to go in favor of the cops. With the deck so stacked against them, most victims didn’t even bother to speak up. Often, they did have drugs or guns, and the fact that the cops lied about the details of the encounter or took some of the seized money for themselves, well, in Baltimore, it was a dirty game in which the ends justified the means.

On the other end of the scale, we have Joyce Carol Oates who plunges herself deep into the consciousness of Marilyn Monroe in her novelised biography of the Hollywood icon, Blonde:

Yet as an adult woman she continued to seek out the movie. Slipping into theaters in obscure districts of the city or in cities unknown to her. Insomniac, she might buy a ticket for a midnight show. She might buy a ticket for the first show of the day, in the late morning. She wasn't fleeing her own life (though her life had grown baffling to her, as adult life does to those who live it) but instead easing into a parenthesis within that life, stopping time as a child might arrest the movement of a clock's hands: by force. Entering the darkened theater (which sometimes smelled of stale popcorn, the hair lotion of strangers, disinfectant), excited as a young girl looking up eagerly to see on the screen yet again Oh, another time! one more time! the beautiful blond woman who seems never to age, encased in flesh like any woman and yet graceful as no ordinary woman could be, a powerful radiance shining not only in her luminous eyes but in her very skin. For my, skin is my soul. There is no soul otherwise. You see in me the promise of human joy. She who slips into the theater, choosing a seat in a row, near the screen, gives herself unquestioningly up to the movie that's both familiar and unfamiliar as a recurring dream imperfectly recalled. The costumes of the actors, the hairstyles, even the faces and voices of the movie people change with the years, and she can remember, not clearly but in fragments, her own lost emotions, the loneliness of her childhood only partly assuaged by the looming screen. Another world to live in. Where? There was a day, an hour, when she realized that the Fair Princess, who is so beautiful because she is so beautiful and because she is the Fair Princess, is doomed to seek, in others' eyes, confirmation of her own being. For we are not who we are told we are, if we are not told. Are we?

For some, this approach is far too intrusive and presumptuous. How can Joyce Carol Oates presume to know what it’s like being in Marilyn Monroe’s head? Does it even sound like Marilyn or Oates in fancy dress? For some, not only is it a bridge too far, it’s a moral transgression, a form of trespass and arguable even worse, it signposts its own artifice and shows the seams of its own construction.

The recent Netflix adaptation of the book, while in some ways faithful to the source material, was also critiqued for being as exploitative about the myth of Marilyn Monroe as Hollywood was in the 1950s and 1960s.

Some of these criticisms land more in film as the representations are more literal and there’s the added dimension of using real people to enact the story, with claims that Ana De Armas was body was exploited by the depictions of nudity. But the book itself has also faced criticism for Oates ‘making up’ scenes and events to satisfy her narrative.

In Oates’s defence, she describes the novel more as a kind of artistic portrait and an emblem of twentieth-century America.

The purpose isn’t to present an scientifically accurate reconstruction of Monroe’s state of being but to use the tools of fiction to speculative and consider what she might’ve been like and by showing her interiority, grant her more agency than give her a voice than had previously been allowed.

It does also beg the question, often levelled at historical fictions, of why bother basing your material on something factual if you’re going to take such creative liberties with it?

In David Grann’s Killers of the Flower Moon, he generally slides between levels 1-3:

The Shoun brothers set up a plank as a makeshift table. From a medical bag, they removed a few primitive instruments, including a saw. The heat slithered into the shade. Flies swarmed. The doctors examined the clothes Anna wore—her bloomers, her skirt—searching for unusual tears or stains. Finding nothing, they tried to determine the time of death. This is more difficult than generally presumed, particularly after a person has been dead for several days. In the nineteenth century, scientists believed that they had solved the riddle by studying the phases a body passes through after death: the stiffening of the limbs (rigor mortis), the corpse’s changing temperature (algor mortis), and the discoloring of the skin from stagnant blood (livor mortis). But pathologists soon realized that too many variables—from the humidity in the air to the type of clothing on the corpse—affect the rate of decomposition to allow a precise calculation. Still, a rough estimate of the time of death can be made, and the Shouns determined that Anna had been deceased between five and seven days.

The doctors shifted Anna’s head slightly in the wooden box. Part of her scalp slipped off, revealing a perfectly round hole in the back of her skull. “She’s been shot!” one of the Shouns exclaimed.

There was a stirring among the men. Looking closer, they saw that the hole’s circumference was barely that of a pencil. Mathis thought that a .32-caliber bullet had caused the wound. As the men traced the path of the bullet—it had entered just below the crown, on a downward trajectory—there was no longer any doubt: Anna’s death had been cold-blooded murder.

Grann’s research included a combination of speaking to decedents and family of the characters in question and other written records. When he does attribute a ‘thought’ or feeling to a character, it appears as if it’s in the moment, a kind of immersive reconstruction but in reality, it’s something he’s learned after the fact and then attributed chronologically.

There are countless other examples. The main thing is – and this counts for first person too and presenting yourself on the page – you don’t always have to be knee-deep in brain matter. In fact, many contemporary authors like Jon MacGregor, Sally Rooney and Cynan Jones do a fantastic job of creating psychologically compelling characters without ever really presenting any interiority.

Keeping distance can ensure you don’t trespass in other people's experience or identity. On the other hand, getting in close can be more immersive and give a sense of what it’s actually like to be that person. It can take more leaps of imagination and creativity to speculate on the unknowable. How you go about this relies on the level of access and permission you have; what kind of material you’re creating and what you personally feel comfortable with.

A good exercise would be to think of the five levels, think of a character in a particular scenario and write their perspective form different levels of narrative distance. See what sticks. See what you like the feel of, which level suits your gaze and the demands of the story.

Hi, the classification of levels is useful in the sense that one can move from what can be known and fact checked (level 1) to possibly be known through observation, like expression on the face, or attitude (Level 2 and maybe level 3), to level four which is contextually conjectured and level 5 imaginative. The question: can tense be used to express some of the nuance and if so how does one keep the 'syntax' or form intact?