The Map and The Territory

How much realism can art bear? On the art of keeping it real and the dangers of keeping it too real.

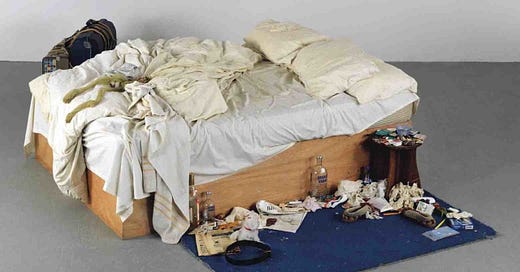

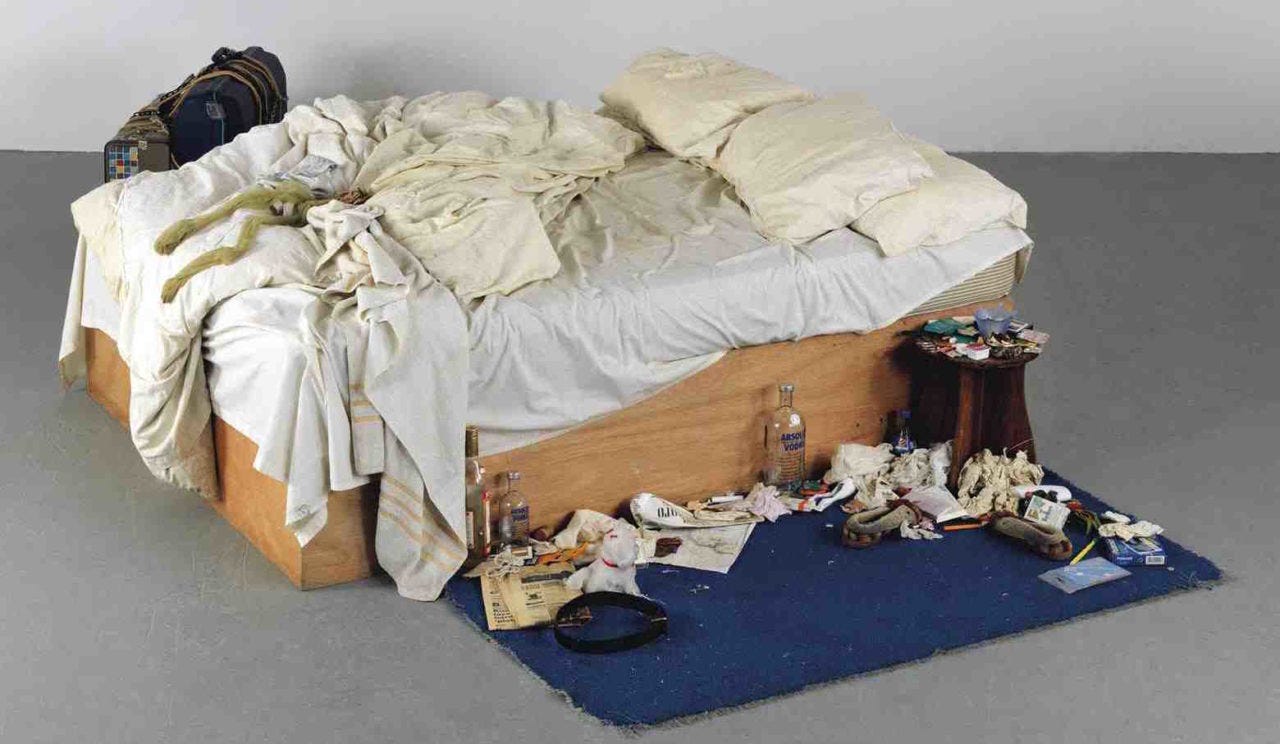

In some of the most lifelike passages of Knausgaard’s My Struggle, it feels like virtual reality and a readerly ennui sets in. What’s the point? Where’s the art? The feeling was akin to the criticism made of Tracey Emin’s bed. To borrow from Adorno’s aesthetics (2014): works of art that appear too expressive appear contrived, yet those which threaten a semblance of the real that is too real risk becoming purely empirical and losing their artistic effect.

It was the same with wrestling: pro wrestling is a morality play, and if it simply mimicked Olympic wrestling, if it were only an imitation of a real sport and not a narrative form in its own right, the characters are lost, the heroes and the villains are lost, the art of pro wrestling and all what people love about it is lost. Without a beginning, a middle and an end with a clear outcome, the vernacular of sequences that create expressive meaning pro wrestling are arbitrary.

At their cores, pro wrestling is moral and novels are ethical. As Susan Sontag (2009) pointed out:

All stories are about battles, struggles of one kind or another, that terminate in victory and in defeat. Everything moves toward the end, when the outcome will be known.

Like I found like in the ring, trying to push the limits of the pro wrestling five act structure, art can only bear so much reality. Grabbing a headlock and holding tight for as long as I could with no beats to the sequence would result in heat from the crowd. They came to see a wrestling match Goddamnnit, not wrestling. The realism that people admire in wrestling, like other art forms, isn’t simply a reproduction of the actual because doing that is actually artless.

Like the map in Jorge Louis Borges’s On Exactitude in Science (1946), a one-paragraph story which describes a fictional map on the same scale as the land it depicts, no story can contain the world and even if it did, it’s not what stories are for. It would simply be a simulation of that what already exists, atemporal, and without meaning. The map is not the territory.

STRONG STYLE

In a provocative essay in Literary Hub, Stephen Marche (2021) drew a distinction between what he considered to the literature of voice and the literature of pose. The dominant idea of the past century was that a writer must find their voice, it must be unique and distinctive, it must be them on the page. As Al Alvarez said, ‘For a writer, voice is a problem that never lets you go... a writer doesn't properly begin until he has a voice of his own.’

For Marche, the literature of the voice is all-consuming, it was the essence of the artistic project and messily human. The authors of voice could be identified within a sentence or two because of their uniqueness. Toni Morrison, Martin Amis, Cormac McCarthy, and so on.

Whereas the literature of pose is just a registering of reality, correct in style and content, fearful of making mistakes, prohibitively self-aware, a stylised pose. In this second category, he would place writers like Sally Rooney, Ottessa Moshfegh and Ben Lerner.

While writers like Rooney turn down the volume of their voices in favour of what’s not said, what’s not written, what’s not on the page, does that mean they don’t have a voice?

Marche says the literature of pose is, ‘the literary product of the MFA system and of Instagram in equal measure’ and he is probably correct in that assessment, though being the product of an MFA system and Instagram is not necessarily a bad thing. Like Marche, I appreciate the big, booming, risk-taking voices of writers of days gone by but the literature of the pose is a literature of reduction, minimalism and subtlety.

It’s remarkable the depth of meaning the writers he derides are capable of which use of such few tools. To me at least, the literature of pose is a response to the long war of attrition against cliché where fresh descriptions feel increasingly laboured, where novelty feels increasingly recycled, repurposed and exhausted.

The novel is dead as a serious technology and plays an increasingly marginal role in the inner life of Western culture. While outwardly being a literature of voice, Knausgård’s struggle against literary pieties and the decline of meaning in the novel. Rather than dial it down, he writes in a style that is free from the untruth of style: set loose with permission to break all the rules of fine writing in his obsession to get to the truth of his experience.

Rooney on the other hand takes the minimal approach: getting herself out of the way, relying more film-like on what is not omitted, the sequencing and choreography of a story and the poses struck artistically.

Stylistically, I come from a more minimalist school of writing but wanted to be set free by self-restraining constraints. Like Knausgård, parts of kayfabe are writing conversationally, with cliches and more attention paid to the sincerity rather than excellence of expression.

But like Rooney, my natural leanings are not as effulgent and overflowing as Knausgård, and my aim was to write invisibly, without attention stretched across every sentence in favour of immediacy, engagement and immersion. Smoking Knausgård’s ‘crack’ was invigorating purely because it was banal, cliché-ridden and sloppy.

In some sense, these techniques are knowingly applied to create the sensation of spontaneity and the contiguousness of the world. The novel form has been a popular form for well over 300 years, how many new ways can there be to describe everyday events and persons?

The liberation of reading Knausgård was in bypassing the conventions of writing-course produced prestige writing and formalist conventions of good taste, in novelising the memoir form in order to strip out needless layers of fictive distance between writer and reader. His overflowing, seemingly uncontrolled Romanticism is a missive against the untruth of stye.

Whereas more genres use elements of The Hero’s Journey, which is itself an externalisation of rite of passage and going out in the world in adulthood, Knausgård inverts the schema, effectively banalizing the mythic structure of Campbell. The role of fantasy and other novels in Knausgård’s reading life are referenced throughout the cycle:

[I] lay back and continued reading 'The Lord of the Rings,' which I had read only two years before but had already completely forgotten. I couldn't get enough of the battle between light and darkness, good and evil. And when the little man not only resisted the superior powers but also showed himself to be the greatest hero of them all, there were tears in my eyes. Oh how good it was.

This banalisation is something that many people apparently do with their own identity narratives. Knausgård’s struggle has been to make his into art.

At his best, Knausgård’s writing moves at a thrillerish pace, combining occasional genre tropes and memoirist digression in a six novel cycle as a whole reads something like The Lord of the Rings, a fantasy novel grounded in the quotidian with in its epic sweep, litigious attitude to world-building, attentiveness to geography and then the overall arc of a young boy engaged in a quest against the dark lord (his father), in a tale of profound transformation writing takes the place of magic, which, like sorcery, is an innate power from another realm. By the end of the cycle, the hero has obtained his object (self-mastery) and can return home.

The traditional liberal humanist view is quasi-religious in that it accepts the premise of an essential self which can be expressed and made real through the writer’s true voice. The understandable mistake liberal humanists have made is to fall for the convincing and self-consoling illusion that the brain plays on us.

As Seth (2021) writes, the self is not an immutable entity that lurks behind the windows of the eyes, looking out into the world and controlling the body as a pilot controls a plane. Yet how do we live otherwise? How do we function as humans if we are to disavow the uniqueness of the self, that we our actions are self-willed and that most of our decisions are made unconsciously?

What’s more, it feels very much like people are different, our children have unique personalities and a sense of volition is central to our self-efficacy. Strong style in literature traditionally would have been strong voice. Whereas strong style writing, as is the case with strong style pro wrestling, is getting as near to the sensation of actual experience without simply becoming a mirror, selling something real as fake in order for the reader to feel real emotion.

Joan Didion’s Kayfabe

Because we may be the immutable souls of traditional liberal humanism and that the coherent self is an illusion, does not mean that there is nothing real communicated in works of literature or that there aren’t individual differences, stable traits that make somebody relatively distinct from one another and uniqueness of experience between people.

What it does change is the sense in which a true autonomous inner self is revealed when in fact it’s more like a self-portrait of a self- portrait generated by the brain. What’s interesting is that we produce these stories and understandings of one another knowing our voices may be distinct to some degree, but rather than be self-authored are largely the result of mind’s perception of our bodily reactions to the world.

In these kayfabe times, it is our tendency as moral creatures to perform our identities through ritual, symbol and performance. The decline of metanarratives has been replaced by the moral certainty of online tribes who have splintered around different sacred narratives of fandoms something like Roman mystery cults.

The search for a strong style is the search for truth and realism in a world in which those terms are increasingly disputed and non-consensual. Even the idea of consensus reality is falling apart. While the feelings that autofictions may elicit are real, and they may contain real truths about the self and the world, like pro wrestling, the practice of autofiction is a works of kayfabe. Necessary illusions we need in order to survive, understand, and flourish.

As Joan Didion (1979) observed:

We tell ourselves stories in order to live... We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the "ideas" with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.

There is a necessary ambivalence to this statement. Like a koan – a riddle without a solution, a paradoxical fable – it can be read as a championing of story and artistry or it can be seen as another way of imposing illusions on reality. Didion wrestles with this agonism throughout the title essay of The White Album.

In any case, we’ve seen that there can be an ethical dimension to telling stories in the sense of ordering events to make sense of the world, as well as a necessity in terms of narrative psychology to spin stories that hold ourselves together but while realism may offer it’s own electrification it is by definition born of inherent artifice.

No novel can ever contain the contents of a whole life. Nor should it. The sensations known to Marcel as he tastes the madeleine cake in Proust’s Swann’s Way requires hundreds of pages to catch the reader up to something that takes micro-seconds to a somebody experiencing a moment of consciousness. Even if it were possible to experience another individuals entire being, what would the point be? Would it even be interesting?

The reader doesn’t have time to coterminously live your life and much of the context is meaningless to them unless you imbue it with meaning. Novels, short stories, personal essays are only ever maps but maps have their uses and enable us the ability to understand, see things and imagine beyond our own perspectives. As Borge’s demonstrates in On Exactitude in Science, a map that bears the same dimensions of the territory doesn’t work:

…In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast Map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

The writing of autofiction excavates experience, offers a hybridity of truth categories and in so doing transforms the individuals in how they see those events and therefore, who they are. The self on the page is not the real self, it is citational but is a performance which constitutes part of the individual in some way. The self on the page is not made of blood and bone but strong style and kayfabe.